This is a long post, but the TL/DR is that derivatives are challenging, irrespective of whether they reference cryptocurrencies or traditional fiat currencies. Both DeFI and centralized exchanges and platforms are likely materially undercapitalized because it appears that novel technologies for processing transactions and aggregating interest do not address management of inherent market, credit and operational risks.

I’ll explain why it is reasonable to allocate significant capital to the risk that your counterparties in a derivative transaction have “problems” or fail to perform as promised.

Crypto Balance Sheets (B/S)

This is the Sam Bankman-Fried’s (SBF) version of FTX B/S:

And below is the FTX balance sheet as submitted to the Chapter 11 process. For simplicity, I’ve consolidated all the balance sheets, excluded Alameda and assumed for the sake of simplicity that inter-entity accounts have been “netted”:

Others have done a great job of ridiculing the first spreadsheet, like here. The boldest part of SBF’s gigantic fraud was the 11th hour capital raise based on essentially a fake balance sheet he just wrote into an excel. He added ~$4bn more in assets than his “unaudited” balance sheet from Sept 30. Cheeky.

The weak financial and operating technology of an exchange that claimed to do “10% of the global crypto volume,” is both scary and disappointing to see. At best, it does not support the view that the future of exchange technology was being built there, at worst it implies that even the most capitalized players in the space still resort to fraud.

They built exceptional software for clients to interact with markets, but just ignored doing basic dual ledger accounting or reconciliation. I guess this makes sense if you spend $1bn on real estate instead!

TradFi B/S

In a traditional bank, at the surface derivatives occupy a tiny portion of the balance sheet - take a look at JPMorgan Chase (JPM):

This is a really high level picture, but derivatives are a small part of “Trading Assets” and “Trading Liabilities,” which make up about 13% of the balance sheet. Net derivatives make up about 1.5% of assets and liabilities(see below chart). The gross figures are impressive in size though: $545bn of “winning” trades and $535bn of “losing” trades.

One way to think about this is that if JPM could perfectly offset all of the future cashflows in their entire portfolio (which is impossible), then over the next ~30 years, the firms counterparties would pay JPM $10bn (measured in todays money) for the lifetime of derivatives executed in the past. This is the realization of profit over time, which has already been reflected as income to date.1

When you dig deeper, it turns out that this superficially small balance is actually much larger. We know this because JPM also has to make what are called Pillar 3 disclosures - which explain how the bank reconciles its capital structure and manages risks, to ensure it does not blow up. Taking a closer look at how derivatives contribute to the Total Leverage Exposure, these derivatives really are treated like a $453bn asset on the balance sheet, and JPM has to both allocate equity capital and hold some aside for regulators in the event that this value vanishes.

The gross derivative assets and liabilities, and the size of assets are staggering and as much as crypto enthusiast can dunk on banks, (for still having branches etc ) the complexity of managing bilateral and centralized derivatives is undeniable.

An example of the complexity

I’ll preface this by saying that this is a fictitious example. JPM may have 10,000 existing bilateral derivative transactions with a single other bank like Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BAML). BAML probably has 100’s if not 1000’s of entities globally which trade in each market.

Let us say 5,000 of those transactions are “in the money” and worth $10bn

The other 5,000 are “out of the money” and worth -$7bn

A net receivable of $3bn is spread across these entities.

A long time ago, participants realized that it would be best for entities like these to enter into what are called master netting agreements. These agreements dictate that if one party defaults, the non defaulting party is allowed to sum up all of the assets and liabilities and “close out” the defaulting party as if it were one single entity and one net number. The entities and transactions referenced in these agreements establish what is called a netting set23

If you take a look at only the “Interest Rate” line in the derivatives chart,

the $10bn gain sits within $ 270bn of “Total derivative receivables”

the $7bn of losses sit in the $240bn of “Total derivative payables”

and because the net position is a gain, the $3bn would sit in the “Net derivative receivables” line and end up on the Asset Side of the Balance Sheet.

At the end of each day, JPM performs this calculation for BAML, alongside each of its other 100k+ clients, and it either sends what it owes or asks for what it is owed as collateral. JPM also employs folks in its Chief Investment Office to manage the myriad risks associated with the fact that people sometimes don’t do what they are supposed to. This was the group that spawned the London Whale back in 2012. Suffice it to say, that it is not particularly easy work and you can sort of get this wrong and "lose" $6.2bn! 4

What does it all mean and how do exchanges work to help alleviate this type of problem?

I was incredibly disappointed to not see an even more complex unpacking of on- chain crypto movement, with off-chain money movement and somewhere in between accounting and reconciliation - this sort of thing would probably be a technology company worth $32bn without even considering 50bps per transaction of trading fees!

I also wonder how many risk managers at cryptocurrency exchanges have either risk exposure management experience, have read or learned about the history of wrong way risk as it may relate to exchange tokens, or have accepted the accounting challenges that arise from derivatives and FX trading.

At a very high level, exchanges serve to provide efficiency and liquidity to markets by providing a central venue to trade instead of the above complex bilateral marketplace. Exchanges are a rigid form of a clearing house where instead of just settling trades on behalf of counterparties and establishing default terms, trading counterparties face the exchange and are guaranteed performance.

Most modern exchanges like the CME solve the challenges of this problem, at least in futures trading, by actually holding as little of customers funds as possible. They do not act as a bank and so a run on the bank is not possible. If Trader A faces Trader B and makes $1mm dollars, generally:

Both Trader A and B had to post some initial margin when their trades were worth 0

When Trader A makes his $1mm, the CME asks trader B for the money at the end of the day and literally wires it to Trader A the same day or multiple times in a day.

Trader A actually doesn’t even know or care who Trader B is.

In a similar way, crypto exchanges provide efficiency and liquidity, but they also tend to act as Custodian for clients profits and they must manage reconciling on-chain activity to the same off-chain financial activity done by traditional exchanges. In the above case, They would hold the balance of Trader A and Trader B, ideally in separate accounts from their own capital.

If the crypto exchange seems to be in trouble, Both Trader A and Trader B can try to close their positions and pull out their money. Facing reduction in general interest on the failing platform, the exchange is left to replace this risk, managing the timing of withdrawals and to do this it needs … capital. This is the point at which most cryptocurrency exchanges have no excess capital and seem to take a little bit of Trader C’s money to resolve the demands of Trader A or B.

Why is custody a big deal?

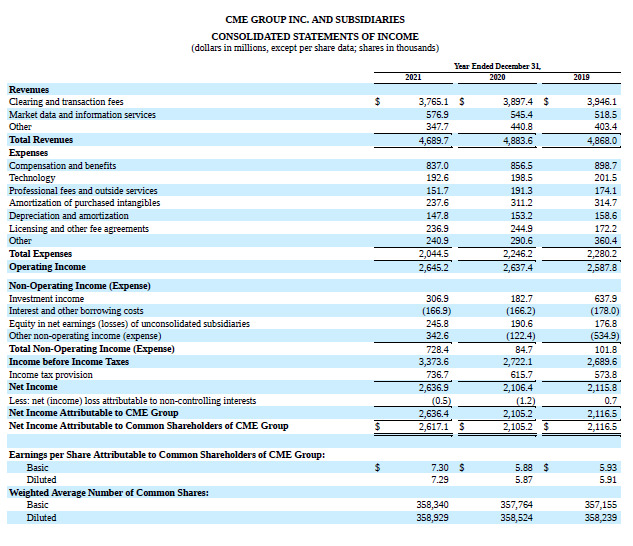

Let’s take a look at some B/S’ again - in this case comparing Coinbase and CME Group. For context, Coinbase earned $7.35bn in revenue in 2021 and CME earned $4.69bn. What is remarkable when you look at the balance sheet is that CME has almost 20 times Coinbase assets while holding 0% in customer funds. In addition, 50% of Coinbase’s $21.3bn in assets are customer funds in custody.

Lets take a look at Coinbase’s balance sheet…

…compared to the CME balance sheet.

This may be misleading, at least at a high level, because Coinbase says they held $278bn of custodial fiat and crypto for customers:

These funds, according to the exchange, are safeguarded via internal controls but no capital is held aside. By comparison, The CME asks its counterparts to post $157bn, to protect against the risk of one member failing and the market price movements in the comparatively low vol fiat currency, rates, equity and commodities markets. The CME also requires members to stand ready to take on the risk of a defaulting counterparty - so they they do not have to do so and trading can continue. The 10-K mentions the word “custody” or “custodian” only in reference to its collateral agreements with broker-dealers and not with respect to customers.

Coinbase does not seem to ask retail customers, or market makers, to post anything for the systematic risk driven by $278bn of custodial assets trading on platform, And most of these crypto currency assets have at least an order of magnitude higher volatility than their fiat cousins.5

Coinbase also largely deals in the spot market, exchanging fiat & cryptocurrencies for settlement in less than 2 business days. This could be one reason that they are less capitalized when compared to the CME, which facilitates longer term derivatives. Their derivative exposures (according to the company) are only formed from “embedded derivatives” where customers post their crypto collateral against fiat loans. In these cases, the company is inherently short a put on the collateral struck at whatever price they are allowed to liquidate clients assets. They seem not to hedge the vol and they get compensated via interest for the counterparty credit risk:

I spent almost 15 years staring at derivatives portfolio’s and derivatives balance sheets and I’ve taken responsibility for a handful of single digit billion dollar derivatives portfolios. In order to discern what confidence I placed on the boundary of possible economic outcomes in a portfolio, I would ask the prior owner to hypothetically convert their portfolio into cash (or frankly any unit which can be used to return equity).

Usually they cant achieve this, and the way they explain why they could not was a good guide for where the “bodies are buried.” The next question I would ask was to stabilizing the P&L - to set the portfolio up in a way that on a daily basis, little value is lost or gained. For challenging derivative portfolios and market makers this is also hard.

We are about to see first hand how the traders at FTX can stabilize a portfolio and turn it into cash to return to customers, and I doubt it is going to be pretty. Even if assets turn out to be greater than liabilities, this is no guarantee that a derivatives portfolio is solvent.

An example of derivatives accounting & economics, if a trader enters into a 10y swap transaction and the market moves such that the value of the swap is $10mm overnight, generally this is called having a “positive mark to market (MTM).” The entity on the other side of the transaction has a “negative MTM.” Even if the contract does not settle for a decade, the institution takes profit and this is shown in the income statement today. because the position is still open, this is reflected on the balance sheet as a net derivative receivable of $10mm. If nothing happens for 10 years the counterparty will eventually pay the trader $10mm in cash - a purely balance sheet related event which has no profit or loss implication.

Beyond this they would also have Initial Margin in the form of High Quality Liquid Assets, and variation margin in the form of cash which can be used to resolve the daily moves in the portfolio and most importantly, the losses (or gains) they would incur if they had to go out into the market and replace all of the risks which would be “unhedged” in a default

A netting set is a collection of entities with the same parent, which JPM has both

a legal agreement which allows it to offset in the money and out of the money transactions…

and an ability to enforce this agreement in the case of default. This can happen for some countries who do not have fantastic rules of law, have a history of ignoring them, or are the federal government and such could change the laws. If JPM is owed $1bn from a nation which historically has changed financial laws or practiced capital controls, it may deem positions with this entity as unenforceable. This is very different from another position with a US bank.

JPM said the trader, Bruno Iksil, was a rogue trader for the record

I admittedly cannot make sense of the Coinbase custodial assets figure. the company says a 100bp move in rates would produce $128mm dollars in revenue from interest income, which makes me assume that if they accrue this annually their custodial assets should be more like $12.8bn in client funds.